Poker Combinations Printable

Summary

Students learn how to use permutations and combinations and when it is appropriate to use each.

In order to be able to read the card correctly, it is not enough to just know the meanings. Understanding the combinations is also important. Remember that while the numbered cards are representative of phases in your life, the court cards, which are the Jacks, Kings, and Queens, are symbolic of the people who are a part of your life. Downlad Poker Hand Rankings PDF Subject: Learn which hands beat which using 888poker's concise poker hand rankings pdf from the worst to the very best, called a Royal Flush. Created Date: 11/4/2015 2:00:04 PM. Five cards which do not form any of the combinations listed above. When comparing two such hands, the one with the better highest card wins. If the highest cards are equal the second cards are compared; if they are equal too the third cards are compared, and so on. So A-J-9-5-3 beats A-10-9-6-4 because the jack beats the ten. Poker Hand Rankings & Charts: Evaluate Your Poker Cards. Before you take us up on our free poker money offer on your way to becoming a World Series of Poker champion, you must first master the basics. The most important in the game is to understand the poker hand strength and rankings.

Background for Teachers

I will just need a pack of cards, a handful of dice (with various numbers of sides) and a whiteboard. Any examples I use will be listed below.

Student Prior Knowledge

Students should have some familiarity with the factorial.

Intended Learning Outcomes

Students will understand the fundamental differences between permutations and combinations and be able to use this knowledge to determine when a permutation is to be used and when a combination is to be used.

Instructional Procedures

I will begin with the dice, looking to teach the fundamental counting principle. I will use a d6, d8, and d20, rolling the smallest die first and ask my students how many combinations of numbers I can get rolling these dice. In rolling the first dice, how many possible numbers can I get? Rolling the second, and then the third? Give students time to work out a solution. Once they have an idea worked up, state the fundamental counting principle: If 2 events occur in order and the first can occur in m ways, while the second can occur in n ways (after the first has occurred) the two events can occur in order in m*n ways. Proceed through more examples, asking specific students. When they respond, I will ask them how they calculated that answer. Let's say I'm working with a drum machine that contains 11 different bass drum samples. On the bass drum channel, I can apply 1 of 4 different effects (distortion, reverb, delay, chorus), how many different bass drum sounds can I get out of this drum machine? Now that I'm done working on my drum machine, I hear the ice cream man coming. He's got 3 different cones and 5 different flavors, how many different ice cream treats can I get? After all of that ice cream, I'm parched. I head to the Kwik-e-mart where they have 21 different kinds of soda on tap with 6 different add-in flavors (cherry, vanilla, etc.), how many different kinds of drink can I get? Do we count no add-in as an option? Once the students seem comfortable with the fundamental counting principle, we can begin discussing permutations. I tell the students that I have just 10 songs on my iPod (a blatant lie, but I don't want them to deal with numbers that are too big). If I put my iPod on shuffle so it will randomly pick a which song plays, and it won't play a song again until it has gone through all of them, I ask my students how many possible sequences of songs are there if I listen until all 10 are played? I don't think 'a lot' is an acceptable answer. If they don't seem to be moving towards an answer, I'll remind them of the principle we just learned. How many possible first songs are there? (psst, 10) Having played the first song, how many possible second songs are there? And so on. There is a connection here between this concept of permutation and the counting principle we've learned. The first song is the first event that can occur, the second song is the second event and on it goes, so we just keep multiplying 10*9*8*...*3*2*1. I will ask if this loooks familiar to anyone? Does it, possibly, make you want to EXCLAIM, 'I know what that is!!!' It's a factorial. Factorials are what we use to calculate permutations. If I have n objects, I can have n! permutations of those objects. That's the key part to remember. If I have 10 songs, I can have 10! (3,628,800) possible sequences of songs while listening on shuffle--seems like a lot for just 10 songs. Now, let's say I want to make a playlist of 3 of those 10 songs. It could be any 3 distinct songs, but the order of the playlist does matter--that is if I have 2 playlists with the same 3 songs, but they are in a different order in each playlist, then those are different playlists. If I just had 3 songs to choose from altogether, how many different playlists of 3 could I make? How many different songs could be the first song, and once that is set how many could be the second, etc. I could end up with 3! (or 6) different playlists. But I've got more than 3 songs to choose from, so if I've got 10 songs on my ipod, how many different songs could be the first and how many could be the second? How many distinct 3-song playlists could I come up with from my massive library of 10 songs? I would have 10*9*8 = 720. So how might we calculate this? How could we come up with a formula that will give me a permutation of r objects selected from n objects. The following section consists of a number of questions designed to guide students to the formula for 'n choose r permutations.' Sufficient wait time should be used after each question to see if the students can come up with the formula on their own. In the case of my playlist, I wanted to make a 3-song playlist (r = 3) from 10 songs (n = 10), and we ended up multiplying the last 3 terms of the factorial together. How could we express that in a general notation, in terms of n and r? How about reduction of fractions. If I wanted to calculate this 'choose 3 from 10' permutation, I might write it as (1*2*3*4*5*6*7*8*9*10)/(1*2*3*4*5*6*7), or more concisely, 10!/7!. Can we relate these back to n and r? The general formula is n!/(n - r)! because by dividing by (n -- r)! we are reducing it to just the last r terms of n! This is how we calculate 'from n objects, choose r.' It is usually written as P(n, r). Now what about dealing cards? I ask, if I deal a poker hand (5 cards) from a deck of 52 cards, how many permutations would I have? Wait for response, students should answer 52!/47! = 311,875,200. That's how many permutations of cards could be dealt. Remind the students, though, that it doesn't matter what order the cards are dealt in. A full house is still a full house, no matter how the cards were dealt. I ask students how many permutations (just in factorial notation) would there be of the 5 cards that are dealt--just looking at those 5 cards alone? It would be 5! permutations, but each of those 5! permutations is just a different arrangement of a single combination. A combination is like permutation, but order doesn't matter. A hand consisting of the ace of spades, queen of hearts, 2 of clubs, jack of diamonds, and 7 of hearts is exactly the same as a hand consisting of the queen of hearts, jack of diamonds, ace of spades, 7 of hearts, and 2 of clubs--and neither will get you anywhere in poker. There are significantly fewer combinations than there are permutations. In fact, in this example, for every 1 combination, there are 5! permutations. Thus, if we were to find a general formula for picking combinations of r objects from a set of n objects, we would come up with P(n, r)/r!, or more formally, C(n, r) = n!/(r!*(n -- r)!). Notice that C(n, r) is how we write combination of r from n. I will then ask my students, what is the important distinction between permutations and combinations? Their answer should be somewhere along the lines of whether order matters or not. Students will pair up into squish groups and then work the following examples. Each group will raise their hands once they've got an answer and I will call on someone once all groups have their hands up. To answer, students need to identify whether a permutation should be used, or a combination, evaluate the answer, and describe the steps they took to arrive at that answer. In how many different ways can 6 people be seated in a row of 6 chairs? (6! = 720, permutation) In how many ways can 3 pizza toppings be chosen from a selection of 12? (12!/(9!*3!) = 220, combination) If 100 people sign up to be beta testers for a new program, and only 4 are chosen, how many different groups of 4 could there be to beta test the program? (100!/(96!*4!) = 3,921,225, combination) In how many ways can a president, vice president, secretary, and treasurer be chosen from a class of 30? (30!/26! = 657,720, permutation) Once this exercise is done, assign homework and let the students be on their way.

Strategies for Diverse Learners

By drawing upon a wide variety of examples, I hope to engage all students by appealing to personal interests. When students get to see this kind of mathematics in action, they are more apt to learn it.

Assessment Plan

tudents will assess themselves and their squish partners during the example exercises at the end of the class. I will also be wary of student responses during this time and try to catch any misconceptions or groups that don't have the right answers. A bell quiz the following class day will consist of the question: How many 5-card hands can be dealt from a deck of 52 cards? We will also cover the homework the next day, allowing students to self-evaluate their work.

Rubrics

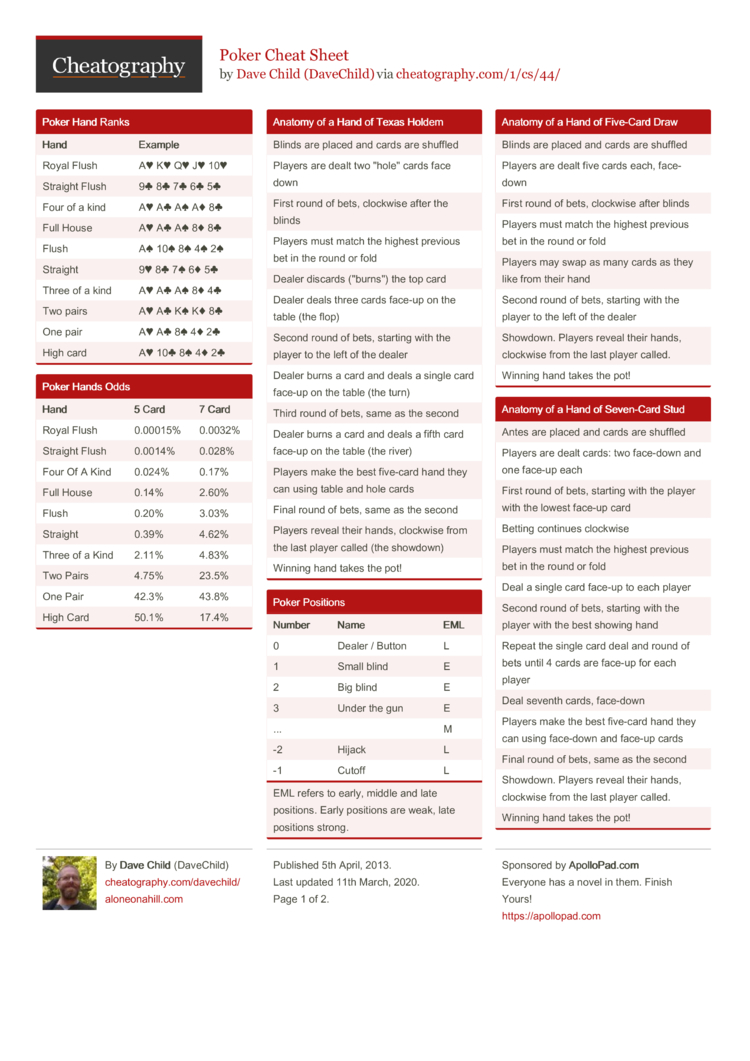

This page describes the ranking of poker hands. This applies not only in the game of poker itself, but also in certain other card games such as Chinese Poker, Chicago, Poker Menteur and Pai Gow Poker.

- Low Poker Ranking: A-5, 2-7, A-6

- Hand probabilities and multiple decks - probability tables

Standard Poker Hand Ranking

There are 52 cards in the pack, and the ranking of the individual cards, from high to low, is ace, king, queen, jack, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2. In standard poker - that is to say in the formal casino and tournament game played internationally and the home game as normally played in North America - there is no ranking between the suits for the purpose of comparing hands - so for example the king of hearts and the king of spades are equal. (Note however that suit ranking is sometimes used for other purposes such as allocating seats, deciding who bets first, and allocating the odd chip when splitting a pot that can't be equally divided. See ranking of suits for details.)

A poker hand consists of five cards. The categories of hand, from highest to lowest, are listed below. Any hand in a higher category beats any hand in a lower category (so for example any three of a kind beats any two pairs). Between hands in the same category the rank of the individual cards decides which is better, as described in more detail below.

In games where a player has more than five cards and selects five to form a poker hand, the remaining cards do not play any part in the ranking. Poker ranks are always based on five cards only, and if these cards are equal the hands are equal, irrespective of the ranks of any unused cards.

Some readers may wonder why one would ever need to compare (say) two threes of a kind of equal rank. This obviously cannot arise in basic draw poker, but such comparisons are needed in poker games using shared (community) cards, such as Texas Hold'em, in poker games with wild cards, and in other card games using poker combinations.

1. Straight Flush

If there are no wild cards, this is the highest type of poker hand: five cards of the same suit in sequence - such as J-10-9-8-7. Between two straight flushes, the one containing the higher top card is higher. An ace can be counted as low, so 5-4-3-2-A is a straight flush, but its top card is the five, not the ace, so it is the lowest type of straight flush. The highest type of straight flush, A-K-Q-J-10 of a suit, is known as a Royal Flush. The cards in a straight flush cannot 'turn the corner': 4-3-2-A-K is not valid.

2. Four of a kind

Four cards of the same rank - such as four queens. The fifth card, known as the kicker, can be anything. This combination is sometimes known as 'quads', and in some parts of Europe it is called a 'poker', though this term for it is unknown in English. Between two fours of a kind, the one with the higher set of four cards is higher - so 3-3-3-3-A is beaten by 4-4-4-4-2. If two or more players have four of a kind of the same rank, the rank of the kicker decides. For example in Texas Hold'em with J-J-J-J-9 on the table (available to all players), a player holding K-7 beats a player holding Q-10 since the king beats the queen. If one player holds 8-2 and another holds 6-5 they split the pot, since the 9 kicker makes the best hand for both of them. If one player holds A-2 and another holds A-K they also split the pot because both have an ace kicker.

3. Full House

This combination, sometimes known as a boat, consists of three cards of one rank and two cards of another rank - for example three sevens and two tens (colloquially known as 'sevens full of tens' or 'sevens on tens'). When comparing full houses, the rank of the three cards determines which is higher. For example 9-9-9-4-4 beats 8-8-8-A-A. If the threes of a kind are equal, the rank of the pairs decides.

4. Flush

Five cards of the same suit. When comparing two flushes, the highest card determines which is higher. If the highest cards are equal then the second highest card is compared; if those are equal too, then the third highest card, and so on. For example K-J-9-3-2 beats K-J-7-6-5 because the nine beats the seven.If all five cards are equal, the flushes are equal.

5. Straight

Five cards of mixed suits in sequence - for example Q-J-10-9-8. When comparing two sequences, the one with the higher ranking top card is better. Ace can count high or low in a straight, but not both at once, so A-K-Q-J-10 and 5-4-3-2-A are valid straights, but 2-A-K-Q-J is not. 5-4-3-2-A, known as a wheel, is the lowest kind of straight, the top card being the five.

6. Three of a Kind

Three cards of the same rank plus two unequal cards. This combination is also known as Triplets or Trips. When comparing two threes of a kind the rank of the three equal cards determines which is higher. If the sets of three are of equal rank, then the higher of the two remaining cards in each hand are compared, and if those are equal, the lower odd card is compared.So for example 5-5-5-3-2 beats 4-4-4-K-5, which beats 4-4-4-Q-9, which beats 4-4-4-Q-8.

7. Two Pairs

A pair consists of two cards of equal rank. In a hand with two pairs, the two pairs are of different ranks (otherwise you would have four of a kind), and there is an odd card to make the hand up to five cards. When comparing hands with two pairs, the hand with the highest pair wins, irrespective of the rank of the other cards - so J-J-2-2-4 beats 10-10-9-9-8 because the jacks beat the tens. If the higher pairs are equal, the lower pairs are compared, so that for example 8-8-6-6-3 beats 8-8-5-5-K. Finally, if both pairs are the same, the odd cards are compared, so Q-Q-5-5-8 beats Q-Q-5-5-4.

8. Pair

A hand with two cards of equal rank and three cards which are different from these and from each other. When comparing two such hands, the hand with the higher pair is better - so for example 6-6-4-3-2 beats 5-5-A-K-Q. If the pairs are equal, compare the highest ranking odd cards from each hand; if these are equal compare the second highest odd card, and if these are equal too compare the lowest odd cards. So J-J-A-9-3 beats J-J-A-8-7 because the 9 beats the 8.

9. Nothing

Five cards which do not form any of the combinations listed above. This combination is often called High Card and sometimes No Pair. The cards must all be of different ranks, not consecutive, and contain at least two different suits. When comparing two such hands, the one with the better highest card wins. If the highest cards are equal the second cards are compared; if they are equal too the third cards are compared, and so on. So A-J-9-5-3 beats A-10-9-6-4 because the jack beats the ten.

Hand Ranking in Low Poker

There are several poker variations in which the lowest hand wins: these are sometimes known as Lowball. There are also 'high-low' variants in which the pot is split between the highest and the lowest hand. A low hand with no combination is normally described by naming its highest card - for example 8-6-5-4-2 would be described as '8-down' or '8-low'.

It first sight it might be assumed that in low poker the hands rank in the reverse order to their ranking in normal (high) poker, but this is not quite the case. There are several different ways to rank low hands, depending on how aces are treated and whether straights and flushes are counted.

Ace to Five

This seems to be the most popular system. Straights and flushes do not count, and Aces are always low. The best hand is therefore 5-4-3-2-A, even if the cards are all in one suit. Then comes 6-4-3-2-A, 6-5-3-2-A, 6-5-4-2-A, 6-5-4-3-A, 6-5-4-3-2, 7-4-3-2-A and so on. Note that when comparing hands, the highest card is compared first, just as in standard poker. So for example 6-5-4-3-2 is better than 7-4-3-2-A because the 6 is lower than the 7. The best hand containing a pair is A-A-4-3-2. This version is sometimes called 'California Lowball'.

When this form of low poker is played as part of a high-low split variant, there is sometimes a condition that a hand must be 'eight or better' to qualify to win the low part of the pot. In this case a hand must consist of five unequal cards, all 8 or lower, to qualify for low. The worst such hand is 8-7-6-5-4.

Deuce to Seven

The hands rank in almost the same order as in standard poker, with straights and flushes counting and the lowest hand wins. The difference from normal poker is that Aces are always high , so that A-2-3-4-5 is not a straight, but ranks between K-Q-J-10-8 and A-6-4-3-2. The best hand in this form is 7-5-4-3-2 in mixed suits, hence the name 'deuce to seven'. The next best is 7-6-4-3-2, then 7-6-5-3-2, 7-6-5-4-2, 8-5-4-3-2, 8-6-4-3-2, 8-6-5-3-2, 8-6-5-4-2, 8-6-5-4-3, 8-7-4-3-2, etc. The highest card is always compared first, so for example 8-6-5-4-3 is better than 8-7-4-3-2 even though the latter contains a 2, because the 6 is lower than the 7. The best hand containing a pair is 2-2-5-4-3, but this would be beaten by A-K-Q-J-9 - the worst 'high card' hand. This version is sometimes called 'Kansas City Lowball'.

Ace to Six

Many home poker players play that straights and flushes count, but that aces can be counted as low. In this version 5-4-3-2-A is a bad hand because it is a straight, so the best low hand is 6-4-3-2-A. There are a couple of issues around the treatment of aces in this variant.

- First, what about A-K-Q-J-10? Since aces are low, this should not count as a straight. It is a king-down, and is lower and therefore better than K-Q-J-10-2.

- Second, a pair of aces is the lowest and therefore the best pair, beating a pair of twos.

It is likely that some players would disagree with both the above rulings, preferring to count A-K-Q-J-10 as a straight and in some cases considering A-A to be the highest pair rather than the lowest. It would be wise to check that you agree on these details before playing ace-to-six low poker with unfamiliar opponents.

Selecting from more than five cards

Note that in games where more than five cards are available, the player is free to select whichever cards make the lowest hand. For example a player in Seven Card Stud Hi-Lo 8 or Better whose cards are 10-8-6-6-3-2-A can omit the 10 and one of the 6's to create a qualifying hand for low.

Poker Hand Ranking with Wild Cards

A wild card card that can be used to substitute for a card that the holder needs to make up a hand. In some variants one or more jokers are added to the pack to act as wild cards. In others, one or more cards of the 52-card pack may be designated as wild - for example all the twos ('deuces wild') or the jacks of hearts and spades ('one-eyed jacks wild', since these are the only two jacks shown in profile in Anglo-American decks).

The most usual rule is that a wild card can be used either

- to represent any card not already present in the hand, or

- to make the special combination of 'five of a kind'.

This approach is not entirely consistent, since five of a kind - five cards of equal rank - must necessarily include one duplicate card, since there are only four suits. The only practical effect of the rule against duplicates is to prevent the formation of a 'double ace flush'. So for example in the hand A-9-8-5-joker, the joker counts as a K, not a second ace, and this hand is therefore beaten by A-K-10-4-3, the 10 beating the 9.

Five of a Kind

When playing with wild cards, five of a kind becomes the highest type of hand, beating a royal flush. Between fives of a kind, the higher beats the lower, five aces being highest of all.

The Bug

Some games, especially five card draw, are often played with a bug. This is a joker added to the pack which acts as a limited wild card. It can either be used as an ace, or to complete a straight or a flush. Thus the highest hand is five aces (A-A-A-A-joker), but other fives of a kind are impossible - for example 6-6-6-6-joker would count as four sixes with an ace kicker and a straight flush would beat this hand. Also a hand like 8-8-5-5-joker counts as two pairs with the joker representing an ace, not as a full house.

Wild Cards in Low Poker

In Low Poker, a wild card can be used to represent a card of a rank not already present in the player's hand. It is then sometimes known as a 'fitter'. For example 6-5-4-2-joker would count as a pair of sixes in normal poker with the joker wild, but in ace-to-five low poker the joker could be used as an ace, and in deuce-to-seven low poker it could be used as a seven to complete a low hand.

Lowest Card Wild

Some home poker variants are played with the player's lowest card (or lowest concealed card) wild. In this case the rule applies to the lowest ranked card held at the time of the showdown, using the normal order ace (high) to two (low). Aces cannot be counted as low to make them wild.

Double Ace Flush

Some people play with the house rule that a wild card can represent any card, including a duplicate of a card already held. It then becomes possible to have a flush containing two or more aces. Flushes with more than one ace are not allowed unless specifically agreed as a house rule.

Natural versus Wild

Some play with the house rule that a natural hand beats an equal hand in which one or more of the cards are represented by wild cards. This can be extended to specify that a hand with more wild cards beats an otherwise equal hand with fewer wild cards. This must be agreed in advance: in the absence of any agreement, wild cards are as good as the natural cards they represent.

Incomplete Hands

In some poker variants, such as No Peek, it is necessary to compare hands that have fewer than five cards. With fewer than five cards, you cannot have a straight, flush or full house. You can make a four of a kind or two pairs with only four cards, triplets with three cards, a pair with two cards and a 'high card' hand with just one card.

The process of comparing first the combination and then the kickers in descending order is the same as when comparing five-card hands. In hands with unequal numbers of cards any kicker that is present in the hand beats a missing kicker. So for example 8-8-K beats 8-8-6-2 because the king beats the 6, but 8-8-6-2 beats 8-8-6 because a 2 is better than a missing fourth card. Similarly a 10 by itself beats 9-5, which beats 9-3-2, which beats 9-3, which beats a 9 by itself.

Ranking of suits

In standard poker there is no ranking of suits for the purpose of comparing hands. If two hands are identical apart from the suits of the cards then they count as equal. In standard poker, if there are two highest equal hands in a showdown, the pot is split between them. Standard poker rules do, however, specify a hierarchy of suits: spades (highest), hearts, diamonds, clubs (lowest) (as in Contract Bridge), which is used to break ties for special purposes such as:

- drawing cards to allocate players to seats or tables;

- deciding who bets first in stud poker according to the highest or lowest upcard;

- allocating a chip that is left over when a pot cannot be shared exactly between two or more players.

I have, however, heard from several home poker players who play by house rules that use this same ranking of suits to break ties between otherwise equal hands. For some reason, players most often think of this as a way to break ties between royal flushes, which would be most relevant in a game with many wild cards, where such hands might become commonplace. However, if you want to introduce a suit ranking it is important also to agree how it will apply to other, lower types of hand. If one player A has 8-8-J-9-3 and player B has 8-8-J-9-3, who will win? Does player A win by having the highest card within the pair of eights, or does player B win because her highest single card, the jack, is in a higher suit? What about K-Q-7-6-2 against K-Q-7-6-2 ? So far as I know there is no universally accepted answer to these questions: this is non-standard poker, and your house rules are whatever you agree that they are. Three different rules that I have come across, when hands are equal apart from suit are:

- Compare the suit of the highest card in the hand.

- Compare the suit of the highest paired card - for example if two people have J-J-7-7-K the highest jack wins.

- Compare the suit of the highest unpaired card - for example if two people have K-K-7-5-4 compare the 7's.

Although the order spades, hearts, diamonds, clubs may seem natural to Bridge players and English speakers, other suit orders are common, especially in some European countries. Up to now, I have come across:

- spades (high), hearts, clubs, diamonds (low)

- spades (high), diamonds, clubs, hearts (low)

- hearts (high), spades, diamonds, clubs (low) (in Greece and in Turkey)

- hearts (high), diamonds, spades, clubs (low) (in Austria and in Sweden)

- hearts (high), diamonds, clubs, spades (low) (in Italy)

- diamonds (high), spades, hearts, clubs (low) (in Brazil)

- diamonds (high), hearts, spades, clubs (low) (in Brazil)

- clubs (high), spades, hearts, diamonds (low) (in Germany)

As with all house rules, it would be wise to make sure you have a common understanding before starting to play, especially when the group contains people with whom you have not played before.

Stripped Decks

In some places, especially in continental Europe, poker is sometimes played with a deck of less than 52 cards, the low cards being omitted. Italian Poker is an example. As the pack is reduced, a Flush becomes more difficult to make, and for this reason a Flush is sometimes ranked above a Full House in such games. In a stripped deck game, the ace is considered to be adjacent to the lowest card present in the deck, so for example when using a 36-card deck with 6's low, A-6-7-8-9 is a low straight.

Poker Combinations Printable Sheet

Playing poker with fewer than 52 cards is not a new idea. In the first half of the 19th century, the earliest form of poker was played with just 20 cards - the ace, king, queen, jack and ten of each suit - with five cards dealt to each of four players. The only hand types recognised were, in descending order, four of a kind, full house, three of a kind, two pairs, one pair, no pair.

No Unbeatable Hand

In standard poker a Royal Flush (A-K-Q-J-10 of one suit) cannot be beaten. Even if you introduce suit ranking, the Royal Flush in the highest suit is unbeatable. In some regions, it is considered unsatisfactory to have any hand that is guaranteed to be unbeaten - there should always be a risk. There are several solutions to this.

Poker Combinations Printable Sheets

In Italy this is achieved by the rule 'La minima batte la massima, la massima batte la media e la media batte la minima' ('the minimum beats the maximum, the maximum beats the medium and the medium beats the minimum'). A minimum straight flush is the lowest that can be made with the deck in use. Normally they play with a stripped deck so for example with 40 cards the minimum straight flush would be A-5-6-7-8 of a suit. A maximum straight flush is 10-J-Q-K-A of a suit. All other straight flushes are medium. If two players have medium straight flushes then the one with higher ranked cards wins as usual. Also as usual a maximum straight flush beats a medium one, and a medium straight flush beats a minimum one. But if a minimum straight flush comes up against a maximum straight flush, the minimum beats the maximum. In the very rare case where three players hold a straight flush, one minimum, one medium and one maximum, the pot is split between them. See for example Italian Poker.

In Greece, where hearts is the highest suit, A-K-Q-J-10 is called an Imperial Flush, and it is beaten only by four of a kind of the lowest rank in the deck - for example 6-6-6-6 if playing with 36 cards. Again, in very rare cases there could also be a hand in the showdown that beats the four of a kind but is lower than the Imperial Flush, in which case the pot would be split.

Poker Combinations Printable

Hand probabilities and multiple decks

The ranking order of poker hands corresponds to their probability of occurring in straight poker, where five cards are dealt from a 52-card deck, with no wild cards and no opportunity to use extra cards to improve a hand. The rarer a hand the higher it ranks.

This is neither an essential nor an original feature of poker, and it ceases to be true when wild cards are introduced. In fact, with a large number of wild cards, it is almost inevitable that the higher hand types will be the commoner, not rarer, since wild cards will be used to help make the most valuable type of hand from the available cards.

Poker Combinations Printable Chart

Mark Brader has provided probability tables showing the frequency of each poker hand type when five cards are dealt from a 52-card deck, and also showing how these probabilities would change if multiple decks were used.